Have you ever stopped mid-snack, banana in hand, and wondered what you’re actually eating? Most of us breeze through life calling it a fruit, assuming it grows on a tree, and never questioning the botanical peculiarities hiding beneath that familiar yellow peel.

But here’s where things get deliciously weird: that banana you’re holding is technically a berry, and it doesn’t grow on a tree at all—it grows on what botanists call an herb. Yes, an herb. The same category that includes basil and parsley also contains one of the world’s largest plants.

If your brain just did a little flip, you’re not alone. This revelation tends to shake people’s understanding of the plant world.

By the end of this post, you’ll understand exactly why bananas occupy this strange botanical category, what makes them so unique, and why these classifications actually matter. You’ll never look at your morning smoothie ingredient quite the same way again.

What Makes a Plant an Herb?

Before we dive into bananas specifically, we need to clear up some confusion about what “herb” actually means. In everyday conversation, we use “herb” to describe plants like cilantro, thyme, or oregano—aromatic plants we add to food for flavor. But in botanical terms, “herb” (or more precisely, “herbaceous plant”) has a completely different definition.

Botanically speaking, an herbaceous plant is any plant that lacks persistent woody tissue. That’s it. The key distinguishing feature is the absence of wood in the stem. Trees have trunks made of wood that persist year after year, getting thicker with age.

Herbaceous plants don’t develop this woody structure. Their stems remain soft, green, and succulent. At the end of each growing season, the above-ground parts of many herbaceous plants die back, though perennials will regrow from their roots.

This botanical definition encompasses an enormous range of plants—from tiny violets to towering sunflowers to massive banana plants. The culinary herbs we’re familiar with just happen to be a small subset of herbaceous plants that we use for flavoring.

Why Banana Plants Are Giant Herbs

Walk past a banana plantation and your eyes will tell you that you’re looking at trees. They can reach heights of 20 to 30 feet, with some varieties towering even higher. That impressive “trunk” looks substantial enough to support the heavy bunches of fruit hanging from it. So how can botanists possibly call this an herb?

The secret lies in that trunk, or what botanists prefer to call a pseudostem—literally, a “false stem.” If you were to slice through it, you wouldn’t find rings of wood like you would in an oak or maple tree. Instead, you’d discover something more like a tightly rolled magazine: layer upon layer of leaf sheaths wrapped concentrically around each other.

Here’s how it works: banana leaves emerge from a growing point at the base of the plant, inside an underground structure called a corm or rhizome. As each new leaf develops, its base forms a sheath that wraps tightly around the growing point and the sheaths of the previous leaves.

These overlapping sheaths stack up and interlock to create what appears to be a solid trunk. The “trunk” is actually the compressed bases of 20 to 30 leaves, furled around each other in a tight spiral.

This pseudostem contains no wood whatsoever. It’s mostly water and soft tissue. Cut one down with a machete (which takes just a few swings), and you’ll see it’s more like slicing through a giant celery stalk than chopping down a tree.

The texture is fibrous but yielding, and it exudes a sticky, latex-like sap that can permanently stain clothing—a frustration familiar to anyone who’s harvested bananas.

The True Stem Hiding Inside

While the pseudostem gets all the attention, the plant’s actual stem is playing hide-and-seek. The true stem starts underground at the rhizome’s growing tip, then travels upward through the center of the pseudostem, completely hidden from view. You won’t see it until months into the plant’s growth cycle.

Eventually, this true stem emerges from the top of the pseudostem carrying the plant’s crowning achievement: the inflorescence, that purple, cone-shaped flower bud that will produce all those bananas.

At this point, the stem that was hidden inside becomes the peduncle—the stalk supporting the developing fruit. Even this stem, however, never develops woody tissue. It remains herbaceous throughout its entire life.

One Crop and Done: The Banana Plant’s Unusual Life Cycle

Here’s another way banana plants differ dramatically from trees: they’re essentially annuals on a larger scale. Each pseudostem produces exactly one crop of bananas, and then it dies. Not the whole plant, mind you—just that above-ground pseudostem.

After the bananas ripen and are harvested (or fall naturally), the pseudostem that bore them shrivels and dies back to the ground.

But the rhizome below remains very much alive. It has been busy producing new shoots called suckers or pups, which emerge from the base of the dying pseudostem. These suckers grow into new pseudostems, which will eventually fruit and die in turn.

This continuous cycle means that a single banana rhizome can remain productive for decades, sending up generation after generation of pseudostems.

Walk through an established banana grove, and you’ll see plants at every stage: young suckers just emerging, adolescent plants with full foliage, mature plants bearing fruit, and dying pseudostems being cut down. It’s a perpetual production line.

This growth pattern also gives rise to the quirky phenomenon of banana plants “walking.” Because each new sucker typically emerges slightly to the side of the parent plant rather than directly beneath it, the productive center of the plant gradually shifts location over time.

Over years, a banana plant can migrate several feet from where it originally started—a mobility no tree can claim.

And Now for the Berry Revelation

If calling a 20-foot plant an herb seems bizarre, calling bananas berries might break your brain entirely. But botanically, that’s exactly what they are.

In botanical terms, a berry is a fleshy fruit produced from a single ovary that contains one or more seeds embedded in the flesh. The fruit has three distinct layers: an outer skin (exocarp), a fleshy middle (mesocarp), and an inner layer surrounding the seeds (endocarp). Bananas check all these boxes.

Each banana develops from a single flower on the inflorescence. The flower’s ovary swells and matures into the fruit we recognize, with a thick yellow skin protecting the soft, creamy flesh inside.

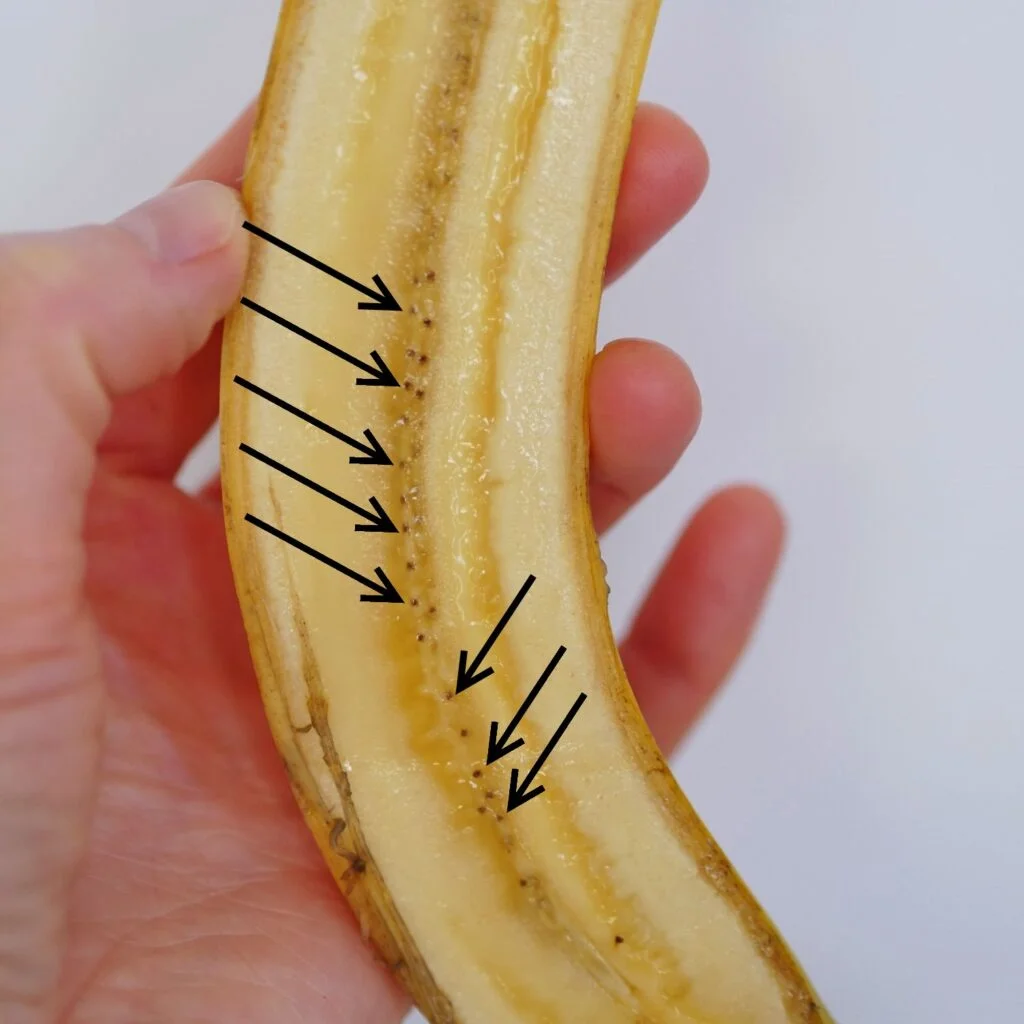

Those tiny black specks running down the center of a banana? Those are the remnants of seeds—shrunken to near-invisibility through centuries of selective breeding, but still present as proof of the fruit’s berry heritage.

This makes bananas relatives of other botanical berries you might not expect: tomatoes, grapes, eggplants, and even watermelons. Meanwhile, those fruits we commonly call berries—strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries—aren’t berries at all by the botanical definition.

Strawberries are accessory fruits (the “seeds” on the outside are the actual fruits), while raspberries and blackberries are aggregate fruits (formed from flowers with multiple ovaries). The botanical world loves to mess with our expectations.

👉 Here’s How to Grow White Strawberries: Pineberry Growing Guide & Care Tips

A Family Connection: Banana Meets Ginger

Banana plants belong to the order Zingiberales and are distant cousins of ginger, turmeric, and cardamom. Once you know this, the family resemblance becomes apparent.

Like ginger, bananas grow from underground rhizomes. Like ginger, they send up leafy shoots rather than developing woody stems. Both plants produce distinctive flowers and thrive in tropical conditions.

This relationship becomes even more evident if you compare a banana plant’s structure to more “exotic” herbs like lemongrass or horseradish. These plants form substantial above-ground growth without any wood, just like bananas—they’re simply operating on different scales.

The Anatomy of a Banana Bunch: Hands, Fingers, and a Troubling Etymology

One of the charming aspects of banana terminology is how we describe the fruit: a cluster of bananas on the plant is called a bunch, each tier or section of that cluster is a hand (typically containing 10-20 bananas), and each individual banana is a finger.

The visual analogy is perfect—the curved bananas do look remarkably like fingers clustered together into hands.

However, the origin of these terms is less charming. Historical records indicate that these names were coined not by the farmers who grew bananas, but by Arab slave traders who also traded in bananas.

This linguistic legacy reminds us that the banana trade, like so many agricultural industries, has deep connections to histories of exploitation and colonialism—connections that persist in modern labor practices on some plantations.

Not Your Average Houseplant: Growing Bananas

The fact that bananas are herbs rather than trees has practical implications for cultivation, particularly in cooler climates. Because herbaceous plants die back seasonally, cold-hardy banana varieties can survive in climates that would kill tropical trees.

Varieties like Musa basjoo (Japanese fiber banana) can survive in USDA zone 5—that’s areas where winter temperatures drop to -20°F. The pseudostem dies back completely with the first hard frost, but the rhizome, buried under a thick layer of mulch, remains dormant through the winter.

When spring returns, new shoots emerge and the cycle begins again. In these cold climates, the growing season isn’t long enough for the plant to produce ripened fruit, but the massive, tropical-looking foliage provides an exotic accent to temperate gardens.

In warmer zones (8-10), cold-hardy varieties like Musa velutina (the pink banana) can complete their full fruiting cycle. These ornamental bananas produce small pink fruits that split open when ripe, revealing flesh full of hard black seeds—a glimpse of what bananas looked like before humans bred them into the seedless varieties we know today.

Growing bananas successfully requires understanding their herbaceous nature. Unlike trees that can tough out periods of stress, banana plants need consistent care:

- Water: As succulent herbs, they’re about 93% water by weight. They need deep, regular watering—especially during hot weather—without waterlogging. Think of them as giant celery stalks that need to stay crisp.

- Nutrients: Without woody tissue to store reserves, they depend on constant nutrient availability. Monthly fertilizing keeps them growing vigorously.

- Soil: Well-drained, organically rich soil is essential. The rhizome and roots need oxygen, so heavy clay soils that stay soggy will cause problems.

- Protection: Those massive leaves shred easily in wind—a vulnerability trees don’t share. Planting in sheltered locations or grouping plants together provides protection.

More Than Just Fruit: The Versatile Banana Plant

Because every part of the banana plant is soft and pliable rather than woody, nearly every part has found uses beyond producing fruit:

- Leaves:

Banana leaves are massive, flexible, and naturally waterproof. Throughout Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Latin America, they serve as biodegradable food wrappers, cooking vessels, serving plates, and roofing material. The leaves impart a subtle, pleasant flavor to food steamed or grilled inside them.

- Flowers:

The large purple banana blossom (also called the banana heart) is edible and tasty. Popular in Southeast Asian cuisines, it has a flavor reminiscent of artichoke hearts and can be eaten raw in salads or cooked in curries and soups.

- Fiber:

The pseudostem’s fibrous tissue can be processed into textiles. In Japan, banana fiber has been woven into fabric for clothing since at least the 13th century.

Different layers of the pseudostem produce fibers of varying fineness—outer layers make durable tablecloths and rugs, while the softest inner fibers create delicate fabric similar to silk. The fiber is also processed into high-quality paper.

- Stems for cooking:

In some South Asian cuisines, the tender inner core of the pseudostem is chopped and cooked as a vegetable, valued for its mild flavor and nutritional content.

None of these uses would be possible with a woody tree trunk. The banana’s herbaceous nature makes it remarkably versatile.

The Cavendish Monoculture and What It Means

The bananas filling supermarket produce sections worldwide are almost exclusively one variety: the Cavendish. This wasn’t always the case.

Until the 1950s, the dominant commercial banana was the Gros Michel (Big Mike), a variety with a richer, sweeter flavor—the taste that inspired artificial banana flavoring, which is why banana candy tastes different from fresh bananas.

But the Gros Michel fell victim to Panama Disease (Tropical Race 1), a soil fungus that devastated plantations globally. The industry switched to the Cavendish, which was resistant to TR1.

Here’s where the banana’s reproductive strategy becomes a vulnerability: because commercial bananas don’t produce viable seeds, every Cavendish banana plant is a clone, propagated from suckers. This means every Cavendish on Earth shares identical genetics—and identical vulnerabilities.

Now, a new strain of the fungus—Tropical Race 4 (TR4)—is spreading, and the Cavendish has no resistance. With no genetic diversity to draw on, the global banana industry faces a potential crisis. Scientists are working on solutions, including genetic modification and breeding programs, but the clock is ticking.

This isn’t just an academic problem. Bananas are the fourth largest crop globally. Over 400 million people depend on bananas and plantains for a significant portion of their daily calories. The crop provides income for millions of farmers.

The herbaceous nature of banana plants means they can’t simply be grafted like fruit trees to introduce new genetics—scientists must start from scratch breeding or engineering resistance.

Why These Classifications Matter

You might be thinking: who cares whether bananas grow on herbs or trees, whether they’re berries or regular fruits? These seem like botanical technicalities without real-world relevance.

But understanding what bananas actually are helps us understand how to work with them. Knowing they’re herbaceous explains why they:

- Can be grown in cooler climates than you’d expect (the above-ground parts can die and regrow)

- Need different care than fruit trees (consistent water and nutrients vs. deep roots and stored reserves)

- Can be harvested for uses beyond fruit (soft tissue throughout, not just in the fruit)

- Face unique disease vulnerabilities (clonal reproduction, no genetic diversity)

More broadly, the banana story reveals how much we misunderstand the natural world through casual observation. What looks like a tree isn’t always a tree. What seems like a simple fruit is actually a berry. These aren’t just semantic games—they reflect real biological differences that matter for cultivation, ecology, and food security.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can I grow bananas indoors as houseplants?

Yes, and they actually make impressive houseplants if you have the right conditions. Dwarf varieties like ‘Dwarf Cavendish’ or ‘Super Dwarf Cavendish’ can thrive indoors with bright light (ideally from a south-facing window), regular watering, monthly fertilizing, and adequate humidity.

They’re unlikely to fruit indoors unless you have a greenhouse or sunroom with exceptional light, but the foliage alone makes a dramatic tropical statement.

- Why do bananas make my mouth itchy?

Bananas contain chitinases, proteins that can cross-react with latex allergens. This is called latex-fruit syndrome. People allergic to latex often experience tingling or itching with bananas, particularly from handling the peel, which contains more of these proteins than the fruit itself. The allergy can also extend to related foods like avocados and kiwis.

- What’s the difference between bananas and plantains?

Both come from the same genus (Musa), so they’re very closely related. The distinction is primarily culinary rather than botanical. Plantains are starchier, firmer varieties typically cooked before eating, while bananas are sweeter and usually eaten raw.

Plantains are a staple starchy food in tropical regions, analogous to how potatoes function in temperate cuisines.

- Do the tiny black specks in bananas ever grow into seeds?

In commercial Cavendish bananas, no. These vestigial seeds are sterile—they can’t germinate. However, wild banana species and some ornamental varieties (like Musa velutina) produce large, hard, viable seeds that can be planted. Commercial bananas must be propagated from suckers because they can’t reproduce sexually.

- How long does it take a banana plant to produce fruit?

From planting a sucker to harvesting fruit typically takes 9 to 18 months, depending on the variety, climate, and growing conditions. In ideal tropical conditions with no seasonal slowdown, this happens faster. In cooler climates or for cold-hardy varieties, it takes longer. The inflorescence takes another 3-6 months from emergence to ripe fruit.

- Are banana peels really useful for anything besides composting?

Despite internet claims about banana peels whitening teeth or removing splinters, most of these uses lack scientific support. The peels do make excellent compost or mulch (they’re rich in potassium), and they can be eaten if cooked properly—some cultures incorporate them into curries or fried dishes. Their best use is probably returning their nutrients to the soil.

The Bottom Line

Bananas are botanical rebels that refuse to fit neatly into our expectations. They’re herbs masquerading as trees, producing berries we call fruit, all while descending from a distinguished ginger family lineage.

These gentle giants of the plant world grow massive herbaceous pseudostems, fruit once, die back, and regenerate—a life cycle more reminiscent of your garden basil than the apple trees in an orchard.

This strange classification isn’t just botanical pedantry. It reflects the banana’s unique biology, explains its cultivation requirements, illuminates its vulnerabilities, and reveals the remarkable diversity hiding within a fruit we thought we knew.

The next time you peel a banana, take a moment to appreciate that you’re holding a berry from one of the world’s largest herbs—a plant that has traveled from the jungles of Southeast Asia to become one of humanity’s most important crops, all while maintaining its herbaceous soul.

Want to deepen your plant knowledge? Start paying attention to what you think you know about common plants—you might discover that tomatoes aren’t vegetables, strawberries aren’t berries, and peanuts aren’t nuts. The natural world is full of delightful surprises for those willing to look beyond the surface.