Have you ever spotted a bright green caterpillar munching away on your garden plants and wondered what it was? Maybe you’ve noticed mysterious holes in your tomato leaves or watched a peculiar green creature inch its way across your sidewalk.

Green caterpillars are among the most commonly encountered backyard visitors, yet they remain mysterious to many of us.

This guide will help you identify the green caterpillars you’re most likely to encounter, understand their fascinating life cycles, and decide whether they’re friends or foes in your garden. By the end, you’ll know which ones to protect and which ones to manage, plus you’ll have gained a new appreciation for these remarkable creatures.

👉 Discover 50+ Common Christmas Tree Bugs: How to Identify, Prevent & Get Rid of Them

Understanding Green Caterpillars: The Basics

Before diving into specific species, let’s establish what makes caterpillars tick. These creatures are the larval stage of Lepidoptera—butterflies and moths—and their sole purpose during this phase is to eat and grow.

Think of them as living eating machines, programmed for one mission: consume enough fuel to power an extraordinary transformation.

The Caterpillar Life Cycle Explained

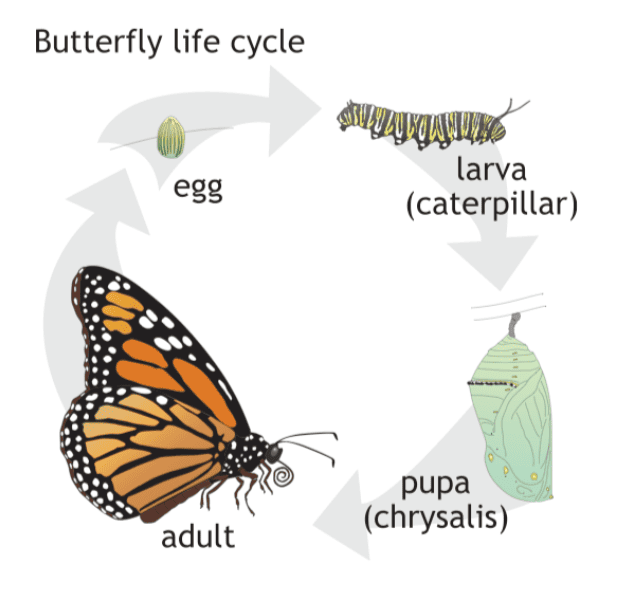

Caterpillars progress through four distinct life stages: egg, larva (the caterpillar itself), pupa, and adult. The larval stage typically lasts three to five weeks, though some species stretch this to months.

During this time, caterpillars molt multiple times—shedding their skin as they outgrow it—progressing through growth stages called instars. Most species go through five instars before pupation.

Here’s what’s remarkable: a caterpillar can increase its body mass by 10,000 times in just a few weeks. To put this in perspective, that’s like a seven-pound human baby growing to the weight of a sperm whale in a month. This explains their notorious appetite and why they can seem to appear suddenly and devastate a plant overnight.

When the caterpillar reaches its final size, it stops eating and enters the pupal stage. Butterfly caterpillars form a hard chrysalis, while most moths spin a silken cocoon.

Inside this protective casing, something extraordinary happens: the caterpillar’s body essentially dissolves into a cellular soup, then reorganizes into a completely different creature. This process, called metamorphosis, remains one of nature’s most remarkable transformations.

Caterpillar Anatomy 101

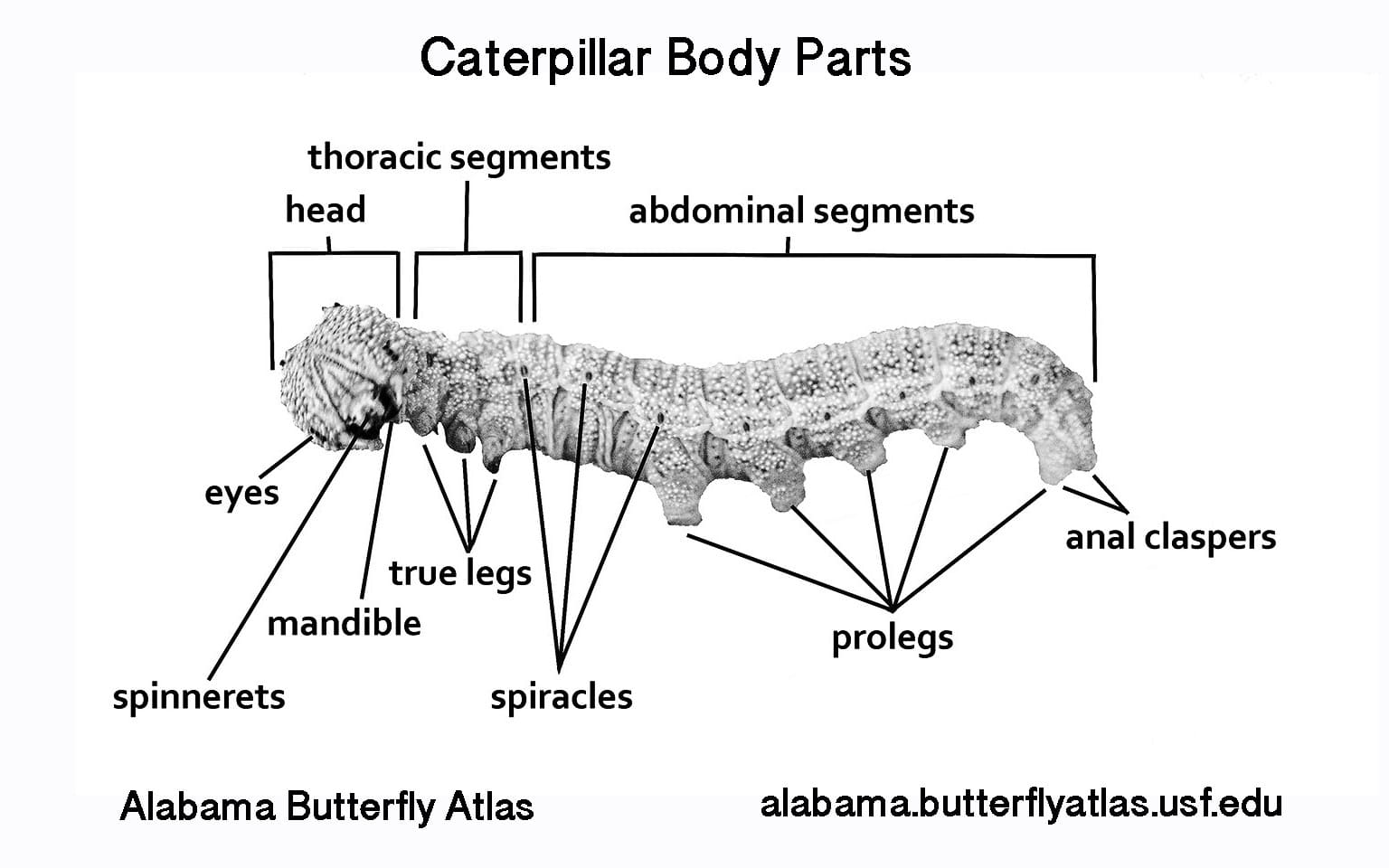

Most green caterpillars share common anatomical features that help with identification. Their elongated, cylindrical body is divided into segments: a head, three thoracic segments, and typically ten abdominal segments.

The head houses powerful chewing mouthparts—unlike adult butterflies and moths that sip nectar with a straw-like proboscis.

Look for six true legs near the head (one pair on each thoracic segment) and several pairs of fleshy prolegs along the abdomen. These prolegs, found only during the caterpillar stage, act like suction cups to help the insect grip stems and leaves.

Most butterfly and moth caterpillars have five pairs of prolegs—four pairs on the mid-abdomen and one pair at the rear.

The green coloration that unites all species in this guide serves a critical survival function: camouflage. Blending seamlessly with leaves helps caterpillars avoid detection by hungry birds, wasps, and other predators.

Not All Green “Caterpillars” Are True Caterpillars

Here’s where things get tricky: some green larvae that look like caterpillars actually aren’t. Sawfly larvae—the immature stage of a primitive wasp group—can fool even experienced gardeners.

The key difference? Count the prolegs. True caterpillars have five or fewer pairs of prolegs, while sawfly larvae typically have six or more pairs. This distinction matters because sawflies respond differently to common caterpillar controls like Bt (more on that later).

Common Green Caterpillars: A Comprehensive Field Guide

The Hornworm Family: Large Green Garden Raiders

The Tomato Hornworm and Tobacco Hornworm

Two closely related species dominate the “most wanted” list for vegetable gardeners: the Tomato Hornworm and Tobacco Hornworm. Both are massive green caterpillars that can reach four inches in length, and both have an insatiable appetite for plants in the nightshade family.

- The Tomato Hornworm (Manduca quinquemaculata) sports a bright green body with eight distinctive V-shaped white markings along its sides and a black horn at its rear.

- Its cousin, the Tobacco Hornworm (Manduca sexta), features seven diagonal white stripes (not V-shaped) bordered in black, with a red or orange horn instead of black.

These hornworms are incredibly difficult to spot despite their size. Their green coloration provides perfect camouflage among tomato leaves, and they typically feed from the interior of the plant outward.

Often, the first sign of their presence isn’t the caterpillar itself but the damage they leave behind: stripped stems, missing leaves, and distinctive dark green droppings on leaves below where they’re feeding.

A single hornworm can strip a tomato plant of all its foliage in just a few days. They feed day and night, and their growth rate is astonishing. What looks like a small green worm one week can become a massive defoliating machine the next. Both species eventually burrow into soil to pupate, emerging as large sphinx moths the following year.

Interestingly, these hornworms become allies when parasitized. If you spot a hornworm covered in white, rice-like cocoons, leave it alone. Those cocoons belong to braconid wasps—beneficial insects that lay eggs inside hornworms. The emerging wasps will parasitize more hornworms and other pest caterpillars, providing natural control.

Other Hawk-Moth Hornworms

Beyond the notorious tomato and tobacco hornworms, several other sphinx moth caterpillars share that characteristic green body and prominent horn.

1. The White-lined Sphinx Moth Caterpillar (Hyles lineata) varies in color from lime green to dark green, often with a series of black lengthwise stripes and yellow-orange spots along its sides. The horn at its rear can be yellow, orange, or black-tipped.

Growing to about 3 inches, this species feeds on an impressive variety of plants—from garden vegetables like tomatoes and grapes to common weeds like purslane. Its adaptability makes it common across North America.

2. The Privet Hawk-moth Caterpillar (Sphinx ligustri) is a hefty green caterpillar reaching up to 3.5 inches long. Its most striking feature is the bold purple and white diagonal stripes along its bright green body, with a curved black horn tipped in yellow at the rear.

The head is distinctively bordered by a yellow collar. These caterpillars primarily feed on privet hedges, but also attack ash, lilac, and jasmine. They’re most common in late summer.

3. The Elephant Hawk-moth Caterpillar (Deilephila elpenor) earns its name from the way its front segments can retract, creating a trunk-like appearance. This chunky caterpillar, reaching 3 inches long, ranges from green to brown with distinctive eyespots near the head.

When threatened, it pulls its head into its swollen thorax, making the eyespots more prominent—a convincing snake mimicry. It feeds primarily on willowherbs and fuchsias from June through September.

4. The Lime Hawk-moth Caterpillar (Mimas tiliae) has a rough, granular green body with pale yellow diagonal stripes. The blue tail horn with a yellow base is diagnostic. Just before pupating, it transforms from green to a striking purplish-pink color.

These caterpillars feed on lime trees (as the name suggests) but also birch, elm, and alder, particularly in urban areas where lime trees line streets.

👉 Read the The Ultimate Guide to Growing Finger Limes: Tips for Cultivation

Giant Silk Moths: The Spectacular Green Giants

Several species of North America’s largest moths begin life as impressive green caterpillars adorned with colorful tubercles and spines.

1. The Luna Moth Caterpillar (Actias luna) is a stunning lime-green larva adorned with yellow lines and small red or orange spots. Fine black spines emerge from small bumps along its body, giving it a textured appearance.

These caterpillars feed on walnut, hickory, birch, and other deciduous trees but rarely occur in numbers that cause noticeable damage. They’re worth celebrating—the adult Luna Moth is one of North America’s most spectacular insects, with pale green wings that can span over four inches.

2. The Polyphemus Moth Caterpillar (Antheraea polyphemus) is a plump, bright green caterpillar that can reach 3 to 4 inches long. Its body features diagonal silver lines or dashes and is adorned with small orange or reddish tubercles. Unlike many sphinx moths, it lacks a horn.

These caterpillars feed on a wide variety of trees—oak, maple, birch, willow—making them common throughout their range. The name comes from the Greek Cyclops Polyphemus, referencing the large eyespots on the adult moth’s wings.

3. The Cecropia Moth Caterpillar (Hyalophora cecropia) starts life yellowish-green but matures to a stunning blue-green. The most distinctive features are the colorful tubercles covering its body—pairs of large blue tubercles along the sides, with yellow, orange, and blue knobs on top.

Each tubercle bears small black spines. Growing to 4 inches long, this is North America’s largest native moth caterpillar. They feed on maple, cherry, birch, and many other deciduous trees.

4. The Imperial Moth Caterpillar (Eacles imperialis) varies considerably in color—some are bright green, others brown or burgundy. Green forms have a smooth body with fine white hairs and a distinctive line of yellowish-white dots with black outlines along each side. They can grow to an impressive 4 to 5 inches long.

Host plants include oak, pine, maple, and sweetgum. Despite their size, they’re rarely abundant enough to cause serious damage.

5. The Hickory Horned Devil (Citheronia regalis) is perhaps the most fearsome-looking caterpillar in North America, though it’s completely harmless. Reaching lengths of 5 to 6 inches, this blue-green giant is covered with black spines and sports impressive curved orange and black horns behind its head—hence the devilish name.

Despite its intimidating appearance, it’s docile and safe to handle. These caterpillars feed on hickory, walnut, pecan, and other hardwoods. The adult form is called the Regal Moth.

👉 Learn about Hummingbird Moth: The Fascinating Insect You Mistake for a Bird or Bee

Swallowtail Caterpillars: Masters of Mimicry

Several swallowtail species feature green caterpillars with fascinating defense mechanisms and visual trickery.

1. The Black Swallowtail Caterpillar (Papilio polyxenes) undergoes a dramatic transformation during its development. Young caterpillars mimic bird droppings—an effective predator deterrent—with a mottled black and white appearance. As they mature, they become bright green with black bands containing yellow or orange spots.

These caterpillars feed on plants in the carrot family: parsley, dill, fennel, and carrots. While they might munch your herb garden, the damage is typically minimal.

When threatened, black swallowtails deploy a fascinating defense mechanism. They extend a forked, orange organ called an osmeterium from behind their head, releasing a distinctly unpleasant odor. Think of it as a tiny, harmless skunk spray designed to discourage birds and other predators.

2. The Spicebush Swallowtail Caterpillar (Papilio troilus) wins the prize for best predator deception. This plump green caterpillar features large false eyespots near its head—yellow and black circles that remarkably resemble a snake’s eyes.

The entire anterior end, when viewed head-on, creates a convincing serpent illusion that stops many predators in their tracks.

These caterpillars feed primarily on spicebush and sassafras, native plants that add ecological value to gardens. Like their black swallowtail cousins, they possess an osmeterium for chemical defense.

3. The Tiger Swallowtail Caterpillar (Papilio glaucus) shares similar defensive tactics with other swallowtails but with less prominent eyespots.

The bright green body features a swollen thorax with yellow spots outlined in black that vaguely resemble eyes, though they’re nowhere near as convincing as the spicebush swallowtail’s. A thin yellow band encircles the body near the head.

These caterpillars feed on wild cherry, tulip trees, willow, and various other deciduous trees.

4. The Zebra Swallowtail Caterpillar (Eurytides marcellus) has a uniquely swollen, humpbacked appearance with the body arching upward between thorax and abdomen. It’s green with yellow and black transverse bands that give it a zebra-striped look.

This species has an extremely limited host range—it feeds exclusively on pawpaw trees. If you have pawpaws, you might encounter these distinctive caterpillars from May through November.

Loopers and Inchworms: The Arching Crawlers

Several green caterpillars move with a distinctive looping motion due to having fewer prolegs than typical caterpillars.

1. The Cabbage Looper (Trichoplusia ni) is notable for its characteristic arching movement. It moves by looping its back because it only has two pairs of prolegs instead of the usual four. This pale green caterpillar, reaching about 1.5 inches at maturity, has an even more voracious appetite than the cabbage white.

A cabbage looper can consume three times its body weight daily, and unlike cabbage whites, loopers feed on a wider variety of vegetables beyond just brassicas.

2. The Winter Moth Caterpillar (Operophtera brumata), also called an inchworm, is a slender pale green caterpillar with two white stripes running lengthwise down its body. Only growing to about an inch long, this invasive species can cause serious damage to trees.

It feeds on oak, maple, beech, willow, and fruit trees, often defoliating branches before gardeners notice the small caterpillars. The looping motion helps distinguish it from other green caterpillars.

3. The Green Cloverworm (Hypena scabra) has a slender, pale green body with white stripes along its sides. Only possessing three pairs of prolegs gives it a characteristic looping movement.

While primarily a pest of agricultural legumes like soybeans and alfalfa, home gardens can see damage to beans, peas, and clover. When disturbed, these caterpillars wiggle violently—a defensive display that’s more show than threat.

Emperors and Prominent Moths: Colorfully Decorated Species

Several moth families produce distinctive green caterpillars with elaborate patterns and textures.

1. The Emperor Moth Caterpillar (Saturnia pavonia) is impossible to mistake for anything else. This vibrant green caterpillar features black rings around each segment, punctuated with yellow and red spots. Stiff, spiky hairs protrude from these spots—not venomous, but capable of causing mild skin irritation if handled roughly.

These caterpillars feed on heather, hawthorn, meadowsweet, and various shrubs. Their size (up to three inches) and distinctive coloring make them one of the most photogenic species.

2. The Pale Tussock Moth Caterpillar (Calliteara pudibunda) is a striking bright green caterpillar with distinctive tufts.

Each body segment has black bands between it and the next, with yellow or whitish hairs forming tufts along the body. A row of yellow tufts runs down the back, and most notably, there’s a bright red or pink tuft at the rear end. These caterpillars feed on various deciduous trees including oak, hop, birch, and hazel.

3. The Angle Shades Moth Caterpillar (Phlogophora meticulosa) can be dull green with whitish dorsal lines running lengthwise. Some forms are brownish-green with red spots along the sides.

This relatively small caterpillar feeds on a wide variety of plants including nettles, dock, and various garden vegetables. The adult moth has distinctive angled wing markings that give it its common name.

4. The Rough Prominent Moth Caterpillar (Nadata gibbosa) has a blue-green to bright green body covered with tiny white dots.

It features a large head capsule, yellow mandibles, and yellow longitudinal stripes. A distinctive red circular dot appears on the side of each segment. This plump caterpillar, growing to about 0.7 inches long, feeds primarily on oak leaves but also eats birch, alder, and maple.

25. The Green-striped Mapleworm (Dryocampa rubicunda), also called the Rosy Maple Caterpillar, has a neon green body with pale green or yellowish stripes running lengthwise.

Black dots appear along the stripes, and short black spines emerge from these dots as the caterpillar matures. The head is distinctly orange-red, and there’s a reddish streak at the rear. Reaching about 2 inches long, these caterpillars feed primarily on maple trees but occasionally attack oaks.

Smaller Green Caterpillars: The Easily Overlooked

Several petite green species can cause surprising damage despite their small size.

1. The Cabbage White Caterpillar (Pieris rapae) appears deceptively innocent—a small, velvety green caterpillar with faint yellow stripes. Growing to just over an inch long, individual caterpillars cause minimal damage.

The problem? They’re rarely alone. Female butterflies can lay dozens of eggs, and the resulting caterpillars blend so perfectly with cabbage leaves that infestations can go unnoticed until significant damage occurs. They feed primarily on leaf undersides, creating holes that gradually expand.

2. The Diamondback Moth Caterpillar (Plutella xylostella) is tiny—only about 0.4 inches long at maturity—but potentially devastating. This pale green caterpillar has a distinctive V-shaped rear formed by its hindmost pair of prolegs. Tiny black spines and white dots cover its body.

Despite their small size, large populations can skeletonize brassica leaves, destroying cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower crops.

3. The Hackberry Emperor Caterpillar (Asterocampa celtis) is a pale green caterpillar with tiny yellowish-white raised bumps covering its body. These bumps form narrow stripes down the back and sides.

The head is green with short green spines, while the top is brown with a pair of small black horns. Two small pointed projections protrude from the rear. Growing to about 1.5 inches, they feed exclusively on hackberry trees, occasionally causing noticeable defoliation.

European Visitors: Introduced Green Species

Several European moths have established populations in North America, bringing their distinctive green caterpillars along.

1. The European Puss Moth Caterpillar (Cerura vinula) is one of the strangest-looking green caterpillars. The bright green body has a triangular head surrounded by a red or pink patch with false eyes.

Two whip-like black tails extend from the rear, and when threatened, these can be thrust forward. Most remarkably, when seriously alarmed, this caterpillar can spray formic acid at attackers—a chemical defense rare among caterpillars. They feed on willow, poplar, and aspen.

2. The Garden Tiger Caterpillar (Arctia caja), while primarily black and orange, has significant greenish coloring when young. Often called a “woolly bear,” it’s covered in dense black and ginger hairs with longer white hairs.

Young larvae show more green base color beneath the hairs. These caterpillars feed on a vast range of plants including nettles, dock, and many garden plants.

Specialty Feeders: Host-Specific Green Caterpillars

Some green caterpillars are so specialized they’ll only eat one type of plant.

1. The Monarch Caterpillar (Danaus plexippus) deserves mention despite not being entirely green. Its green base color is dramatically striped with black and yellow bands, and it sports two pairs of black tentacle-like structures—one pair near the head, another near the rear.

These caterpillars feed exclusively on milkweed plants and have become symbols of conservation efforts. The milkweed diet makes them toxic to predators, a defense they retain as adult butterflies.

2. The Genista Broom Moth Caterpillar (Uresiphita reversalis) is a yellowish-green caterpillar flecked with black and white dots. Long, fine white hairs stick out from each spot, giving it a spiky appearance.

It feeds specifically on broom plants, Texas mountain laurel, lupine, and related legumes. While not typically a garden pest, it can occasionally appear on ornamental plantings of these species.

3. The Copper Underwing Moth Caterpillar (Amphipyra pyramidea) resembles a hornworm but lacks the true horn, having instead a large protruding hump at the rear.

Starting translucent pale green, it develops a yellow stripe along its sides as it matures, eventually turning darker green. This caterpillar characteristically lifts the front part of its body when resting. It feeds on various deciduous trees and shrubs including apple, cherry, maple, and oak.

Reading the Damage: Understanding Caterpillar Feeding Patterns

Learning to recognize caterpillar damage helps you detect problems early, often before you spot the culprits themselves. Different feeding patterns provide clues about which species you’re dealing with.

Defoliation is the most obvious symptom—entire leaves or sections of leaves disappear. Hornworms often strip entire branches, leaving only stems. Cabbage loopers and cabbage whites create irregular holes in leaves, typically starting from the edges or undersides. Large populations can reduce plants to skeletons, with only veins remaining.

Leaf window panes appear when caterpillars feed on one surface of a leaf, leaving the opposite surface intact. Young caterpillars often feed this way before their mouthparts are strong enough to chew through entire leaves. This creates translucent patches where leaf tissue is gone but the “skin” remains.

Frass accumulation offers another telltale sign. Frass—caterpillar droppings—appears as small, dark pellets that accumulate on leaves below feeding sites. Heavy frass accumulation on lower leaves often indicates a significant infestation above, even if you haven’t spotted the caterpillars yet.

Silk webbing signals certain species. Some caterpillars, like young cabbage loopers, may create small silk shelters by folding leaves. Fall webworms (a hairy species) create extensive communal webs at branch tips, though these are less common in vegetable gardens.

The key is catching problems early. A few small holes in leaves rarely threaten plant health, but exponential growth means a couple of caterpillars can become dozens within weeks. Check plants every few days during peak caterpillar season—late spring through early fall.

Safety First: Are Green Caterpillars Dangerous?

The vast majority of green caterpillars pose no threat to humans. Most are soft-bodied, harmless creatures you can handle without concern. However, a few notable exceptions demand caution.

1. The Io Moth Caterpillar (Automeris io) is perhaps the most dangerous green caterpillar you’ll encounter. Despite its beautiful lime-green color with red and white racing stripes, this caterpillar is covered in clusters of venomous spines that branch like tiny pine trees.

Even a light brush against these spines breaks them off in your skin, releasing venom that causes immediate, intense pain. The burning sensation can last several hours and may be accompanied by swelling, redness, and numbness. People describe the pain as similar to a severe bee sting, but more persistent.

2. The Saddleback Caterpillar (Acharia stimulea), though primarily brown, has green patches and venomous spines at both ends and along its sides. Contact produces immediate, sharp pain followed by swelling and potential nausea.

General safety guidelines help you avoid problems:

Smooth-bodied green caterpillars without obvious spines or dense hair are almost always safe to handle. The hornworms, swallowtail caterpillars, and loopers fall into this category. Their “horns” and spines are merely ornamental—soft projections that can’t puncture skin or deliver venom.

Hairy or spiny caterpillars deserve respect. Even species without venom can cause mechanical irritation—their stiff hairs can poke skin and cause itching or mild rashes in sensitive individuals.

Brightly colored caterpillars, especially those with multiple warning colors (like the Io moth’s green with red stripes), often signal danger. In nature, bright colors advertise toxicity or defensive capabilities.

If you’re stung, act quickly. Use tape to remove any embedded spines or hairs, pressing it firmly against the affected area and pulling away. Wash thoroughly with soap and water, then apply ice to reduce pain and swelling.

Over-the-counter antihistamines and pain relievers help manage symptoms. Seek medical attention if you experience spreading pain, difficulty breathing, or signs of allergic reaction.

For most people, the bigger danger from caterpillars isn’t to humans but to plants. Even beneficial species can occasionally appear in large numbers and cause unexpected damage.

The Pest or Pollinator Decision: A Framework for Management

Here’s the central question every gardener faces: when you spot a green caterpillar, should you remove it or let it be? The answer requires balancing ecological awareness with practical garden management.

Understanding Thresholds: When Damage Becomes Unacceptable

First, accept this truth: a healthy garden will have some leaf damage. Holes in foliage are signs of a functioning ecosystem, not necessarily a crisis. The question isn’t whether damage exists, but whether it’s reached a threshold that matters.

For ornamental plants, aesthetic tolerance guides decisions. A few caterpillars on a large oak tree will cause unnoticeable damage—the tree has thousands of leaves and robust health. Even losing 10-15% of foliage won’t harm established trees and shrubs.

Many gardeners find that “imperfect” gardens with signs of life are more interesting than sterile, unblemished landscapes.

For vegetable crops, yield protection drives choices. Young seedlings are vulnerable—a single hornworm can destroy a newly transplanted tomato. But mature, established plants can tolerate surprising amounts of defoliation.

Tomato plants can lose 30-40% of their foliage without significant yield reduction. Leafy vegetables like cabbage and lettuce are less forgiving—visible caterpillars on these crops warrant removal.

Consider the caterpillar’s identity. Beneficial species like swallowtail caterpillars rarely occur in destructive numbers. If you find one or two on your parsley, consider leaving them. You’ll sacrifice a bit of herb harvest but gain beautiful butterflies.

Pest species like hornworms and cabbage loopers deserve less tolerance—they multiply rapidly and cause cascading damage.

Evaluate the timing and plant life stage. Caterpillars found on plants setting fruit are more problematic than those on mature plants past peak production. A hornworm in July on tomatoes heavy with ripening fruit is concerning; the same caterpillar in September after harvest is less urgent.

Integrated Pest Management: A Layered Approach

Effective caterpillar management uses multiple strategies, prioritizing the least disruptive methods first.

Prevention forms your first line of defense

Row covers made of lightweight fabric prevent butterflies and moths from laying eggs on plants. These work exceptionally well for brassicas, where you can cover crops from transplant to harvest.

The key is ensuring covers float above plants without restricting growth, and securing edges so insects can’t slip underneath.

Companion planting may deter some pests, though scientific evidence varies. Strong-smelling herbs like rosemary, thyme, and sage planted among vegetables may confuse egg-laying females searching for host plants by scent. Even if the effect is modest, these herbs benefit gardens in multiple ways.

Regular monitoring catches problems when they’re manageable. During peak season—late May through September in most regions—walk through your garden every two to three days. Flip leaves to check undersides where many species hide during the day. Look for eggs, tiny newly-hatched caterpillars, frass accumulation, and feeding damage.

Manual removal

Manual removal remains highly effective for larger caterpillars. Early morning or evening are prime times—many species are most active then and easier to spot. Drop collected caterpillars into soapy water, which quickly and humanely kills them. For squeamish gardeners, wearing gloves makes the task easier.

Check both sides of leaves systematically, working from the ground up. Caterpillars often congregate on middle-aged leaves—not the newest growth or oldest leaves, but the tender mid-stage foliage. On tomatoes, inspect the area where stems meet the main stalk, a favorite hornworm hiding spot.

Biological controls

Biological controls harness nature’s pest management systems. Encouraging natural predators creates sustainable, long-term control.

Birds are voracious caterpillar consumers—a single chickadee pair can remove thousands of caterpillars during the nesting season. Provide bird houses, water sources, and native plants that produce berries and seeds to support breeding populations.

Parasitic wasps deserve special appreciation. These tiny, non-stinging insects lay eggs in or on caterpillars. The emerging wasp larvae consume the host from inside, eventually killing it.

Many species are commercially available, but native populations establish themselves in diverse gardens with nectar sources. Flowers with tiny blossoms—sweet alyssum, dill, fennel, and yarrow—provide the nectar adult parasitic wasps need.

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) represents the gold standard for organic caterpillar control. This naturally occurring soil bacterium produces proteins toxic to caterpillars but harmless to humans, pets, and beneficial insects like bees and ladybugs.

When caterpillars ingest Bt-treated foliage, the bacteria release toxins in their gut that cause them to stop feeding and die within a few days.

Bt works best on young caterpillars—those in early instars before they’ve caused significant damage. Application timing matters. Spray in the evening after bees have stopped foraging, and reapply after rain or heavy dew.

Coverage is critical—Bt must contact the caterpillar or be ingested on leaf surfaces. Spray both upper and lower leaf surfaces thoroughly.

Different Bt strains target different pests. Bt kurstaki (Btk) specifically targets moth and butterfly caterpillars but won’t harm sawfly larvae. This specificity is both a strength and limitation—you’re controlling the exact pest without broader ecosystem disruption, but you must correctly identify what you’re treating.

Chemical pesticides

Chemical pesticides should be an absolute last resort in home gardens. Broad-spectrum insecticides kill beneficial insects alongside pests, disrupting natural control systems and often creating worse problems long-term.

If you must use chemical control, select products specifically labeled for caterpillars and safe for use on edible crops. Follow all label directions precisely, paying attention to pre-harvest intervals—the required waiting period between application and harvest.

Supporting Beneficial Caterpillars

While managing pests, create spaces for beneficial species. This dual approach maintains garden productivity while supporting biodiversity.

Plant diversity is fundamental. Different caterpillars need different host plants.

- Monarch caterpillars require milkweed—without it, they cannot complete their life cycle.

- Swallowtails need plants in the carrot and citrus families. Luna moths feed on deciduous trees.

A diverse plant palette supports a diverse caterpillar community, which in turn supports birds, butterflies, and moths.

Consider designating sacrifice plants—a few herbs or native plants where you tolerate any caterpillar activity.

- Plant extra parsley, dill, and fennel specifically for swallowtail caterpillars.

- Grow milkweed in a dedicated bed for monarchs.

This strategy concentrates beneficial caterpillars where they’re welcome and may reduce their presence on crops you want to protect.

Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides that create dead zones. Pyrethroid insecticides, neonicotinoids, and other common chemicals persist in the environment and kill indiscriminately.

Gardens treated with these products may be caterpillar-free, but they’re also devoid of the beneficial insects, pollinators, and wildlife that make gardens vibrant ecosystems.

Leave some wild areas if space permits. A corner of unmowed grass, a brush pile, native wildflowers allowed to grow freely—these refuges support native caterpillars and the creatures that depend on them.

Research shows that 70% of native bird species rear their young on insect protein, primarily caterpillars. Supporting caterpillars supports the entire food web.

The Bigger Picture: Caterpillars in the Ecosystem

Understanding caterpillars’ ecological roles helps us appreciate them beyond their impact on our gardens. These creatures are threads in a complex tapestry of interconnected life.

Caterpillars are the primary converter of plant material into animal protein in terrestrial ecosystems. They consume vegetation and transform it into concentrated nutrients that fuel food webs.

Without caterpillars, most songbirds couldn’t raise their young—studies show that chickadees, warblers, bluebirds, and other insectivorous birds rear their nestlings almost exclusively on caterpillars. A single brood of chickadees consumes between 6,000-9,000 caterpillars from hatching to fledging.

Beyond birds, countless other predators depend on caterpillars. Spiders, wasps, ground beetles, assassin bugs, and other beneficial insects prey on caterpillars. Bats consume many species of adult moths, but they also eat caterpillars when available. This predator-prey relationship controls caterpillar populations naturally while supporting biodiversity.

Caterpillars influence plant evolution and diversity. Their feeding pressure has driven plants to develop defensive compounds—the very chemicals we value in medicinal and culinary herbs often evolved as anti-caterpillar defenses.

Caffeine in coffee, salicylic acid (aspirin) in willow, and countless other compounds exist because plants and caterpillars have been in an evolutionary arms race for millions of years.

Some caterpillars have become so specialized that they can only feed on plants containing specific toxins, actually requiring these compounds for their own defense. The monarch-milkweed relationship exemplifies this: monarchs not only tolerate milkweed toxins but accumulate them for protection, advertising their toxicity with bright colors.

Pollination services from adult butterflies and moths represent significant ecosystem benefits. While bees get most attention, lepidopterans pollinate many plant species, particularly those with deep, tubular flowers that exclude other insects. Some plants, like certain evening primrose species, rely primarily on moth pollination.

When we make decisions about caterpillar management, we’re participating in these ecological relationships. A garden that supports some caterpillar activity—tolerating modest foliage damage—contributes to regional biodiversity and ecosystem health in ways that purely ornamental or chemically-maintained landscapes cannot.

Creating a Balanced Garden: Living with Caterpillars

The goal isn’t a caterpillar-free garden—such spaces are ecological deserts. Instead, aim for balance: protecting your crops and ornamentals while supporting beneficial species and the creatures that depend on them.

- Accept imperfection as a feature, not a bug.

Leaves with holes tell stories of a garden integrated into the natural world. Many gardeners find that embracing this imperfection brings unexpected joy—watching a swallowtail caterpillar develop, discovering a chrysalis, witnessing the first flight of a newly emerged moth.

- Create zones with different management intensities.

Your vegetable garden might receive active caterpillar management with row covers, handpicking, and Bt applications. A nearby pollinator garden could be a refuge where caterpillars roam freely. Ornamental beds might fall somewhere in between, with occasional intervention only for severe infestations.

- Time your plantings to minimize pest pressure.

In regions with distinct caterpillar seasons, early planting often allows crops to mature before peak pest activity. Succession planting provides continuous harvest while distributing risk—if one planting suffers damage, others remain productive.

- Build soil health to support plant vigor.

Healthy plants withstand caterpillar damage better than stressed ones. They grow more vigorously, replacing lost foliage and maintaining productivity despite moderate feeding pressure. Compost, mulch, appropriate watering, and avoiding over-fertilization all contribute to plant resilience.

- Connect with community.

Join local garden clubs, native plant societies, or online groups focused on your region. These communities share knowledge about local caterpillar activity, identification help, and management strategies proven effective in your specific climate and conditions.

Many areas have citizen science projects monitoring butterfly and moth populations—participating connects you to larger conservation efforts.

Remember that caterpillar populations fluctuate naturally. A year with high hornworm pressure often follows with a year of low activity as parasites and predators catch up.

Weather patterns, natural enemy populations, and countless other factors create these cycles. A long-term perspective helps you weather the occasional bad year without overreacting.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q: Do all green caterpillars turn into green butterflies or moths?

A: No! Caterpillar color rarely matches adult coloring. Bright green hornworms become gray-brown moths, while green swallowtail caterpillars become black butterflies with yellow markings.

- Q: Why are there holes in my plants but no caterpillars visible?

A: Many caterpillars feed at night or hide during the day. Check the undersides of leaves or inspect plants after dark with a flashlight.

- Q: Can I raise a caterpillar I found?

A: Yes! Place it in a well-ventilated container with fresh leaves from the plant you found it on. Clean the container daily and provide fresh food. Many people find watching the metamorphosis educational and rewarding.

- Q: How long do caterpillars stay caterpillars?

A: Most caterpillars remain in the larval stage for 2-5 weeks, though some species overwinter as caterpillars and can remain in this stage for many months.

- Q: Are green caterpillars good for my garden?

A: It depends! While they consume plants, caterpillars are essential food sources for birds and other wildlife. Adult butterflies and moths pollinate flowers. The key is balance—a few caterpillars are fine, but large infestations of pest species need management.

Final Thoughts: Embracing the Transform-ers

Green caterpillars represent one of nature’s most remarkable transformations—from crawling leaf-eater to flying pollinator. While some species will challenge your patience as a gardener, others offer opportunities to witness incredible biology up close.

The key is learning to distinguish friends from foes. Not every chewed leaf signals disaster. Sometimes, sharing a few leaves with these fascinating creatures means inviting more butterflies and moths into your garden while supporting the broader ecosystem.

Next time you spot a green caterpillar in your yard, pause before reaching for pesticides. Take a moment to identify it, understand its role, and make an informed decision about whether it stays or goes. You might just find yourself captivated by these small but spectacular creatures.

Remember: every butterfly was once a caterpillar, and every healthy garden has room for a little wildness. The occasional chewed leaf is a small price to pay for the magic of metamorphosis.

Have you encountered a green caterpillar you couldn’t identify? Share your photos in the comments below, and let’s work together to solve the mystery!