Picture this: It’s a crisp October morning, and you’re walking through your garden with a cup of coffee, surveying the season’s end. While your neighbor is already planning next year’s seed orders and wondering where to store his rototiller, you’re calmly brushing soil off a handful of Jerusalem artichokes that practically harvested themselves.

This is the magic of perennial root vegetables—the garden’s equivalent of a good investment that keeps paying dividends year after year.

If you’ve ever felt exhausted by the annual cycle of planting, weeding, and replanting your vegetable garden, you’re not alone. What if I told you there’s a whole category of vegetables that you plant once and then harvest for years, sometimes decades?

Welcome to the world of perennial root vegetables—your ticket to a more sustainable, less labor-intensive, and incredibly rewarding garden.

What Are Perennial Root Vegetables?

Think of perennial root vegetables as the wise old trees of the vegetable world. While annual vegetables live fast and die young (looking at you, radishes), perennials are in it for the long haul. They’re plants that live for three or more years, developing extensive root systems that store energy and nutrients underground.

Unlike their above-ground cousins—tomatoes, lettuce, beans—these underground treasures include everything from the familiar (asparagus, rhubarb) to the exotic (skirret, oca). What they all share is an ability to survive winter, emerge stronger each spring, and reward patient gardeners with increasingly abundant harvests.

The “root” part is a bit of a generous interpretation—we’re including any perennial plant where you harvest something from below ground, whether it’s technically a root, tuber, bulb, or rhizome. Think of it as your underground pantry that restocks itself.

Explore Top 44 Perennial Flowers & Plants for Year-Round Garden Color

Why Your Garden (and Your Back) Will Thank You

The Lazy Gardener’s Dream

I learned about the power of perennial vegetables the hard way. Three years ago, I threw out my back during spring planting season—right when I should have been sowing my annual root crops. Instead of missing the season entirely, I focused on the corner of my garden where I’d planted Jerusalem artichokes and walking onions the previous fall.

Not only did these plants emerge without any help from me, but they produced more food than I’d ever gotten from the same space planted with annual crops. That injury taught me that sometimes the best gardening strategy is the one that requires the least work.

The Sustainability Superpower

Perennial root vegetables are like having a savings account in your backyard. Their deep, established root systems deliver multiple benefits: they can reach moisture deep in the soil making them naturally drought-resistant, they improve soil structure and add organic matter as their roots decompose, they keep carbon locked in the soil year-round instead of releasing it through annual tilling, and they provide consistent habitat for beneficial soil organisms.

Financial Sense That Adds Up

Let’s do some quick math. A packet of carrot seeds might cost $3 and need replacing every year. A single asparagus crown costs about $5 but produces for 15-20 years. Even if you only harvest 10 spears per plant per year (a conservative estimate), you’re looking at hundreds of spears over the plant’s lifetime—try buying that at the grocery store!

Getting Started: Your Perennial Root Vegetable Journey

Start Small, Think Big

The biggest mistake new perennial vegetable gardeners make is trying to plant everything at once. Remember, these plants will be in your garden for years or decades. Start with 2-3 varieties that match your climate, cooking habits, and available space.

I recommend beginning with what I call the “Gateway Three”: asparagus (everyone knows how to use it), rhubarb (productive and nearly indestructible), and Egyptian walking onions (fascinating to watch and continuously useful).

Location, Location, Location

Unlike annual vegetables that you can move around each season, perennials are making a permanent home in your garden.

Consider sun requirements (most need at least 6 hours of direct sunlight), space at maturity (that cute asparagus crown will become a 4-foot-wide patch), access for harvest (you’ll be visiting these spots for years), and water access for consistent moisture during establishment.

Find out What’s the Difference Between Annuals, Perennials, and Biennials?

35+ Perennial Root Vegetables Every Gardener Should Know

-

Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis)

Zones: 3-8 | First Harvest: Year 3 | Lifespan: 15-20 years

The crown jewel of perennial vegetables. Yes, you have to wait three years for your first real harvest, but once established, a well-maintained asparagus bed will feed your family every spring for decades. Start with disease-resistant varieties like ‘Jersey Giant’ or ‘Purple Passion’ to avoid common pitfalls.

Growing from: One-year-old crowns are most reliable, though seeds are possible but slower. Plant crowns 12-18 inches apart in trenches 6-8 inches deep, gradually filling in as plants grow.

-

Rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum)

Zones: 3-8 | First Harvest: Year 2 | Lifespan: 10+ years

Rhubarb is the gift that keeps on giving. Once my grandmother’s rhubarb patch got established, it became legendary in our neighborhood. She’d harvest armloads of tart, crispy stalks every spring, make dozens of pies, and still have enough to share with half the block. Choose low-chill varieties like ‘Victoria’ or ‘Cherry Red’ for warmer areas.

Growing from: Crowns or root divisions work best. Seeds are possible but variable. Remember: only harvest the stalks—the leaves contain toxic levels of oxalic acid.

-

Jerusalem Artichokes/Sunchokes (Helianthus tuberosus)

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Indefinite

These are the rabbits of the perennial vegetable world—they multiply enthusiastically. The tubers taste like a cross between a potato and a water chestnut, with a slight nutty sweetness. Fair warning: they can become invasive, so consider planting them in a dedicated bed or large containers.

Growing from: Tubers planted 2-4 inches deep, 12-18 inches apart. ‘Fuseau’ and ‘Mammoth French White’ are good varieties to start with. Some people experience digestive issues with raw sunchokes—cooking them longer (roasting for 45+ minutes) breaks down the inulin and makes them easier to digest.

Read The Complete Guide to Growing Artichokes in Any Climate: Tips for Every Gardener

-

Egyptian Walking Onions (Allium × proliferum)

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Indefinite

The circus performers of the onion world! These fascinating plants produce small bulbs at the top of their flower stalks, which eventually get heavy enough to bend the stalk over, “planting” themselves a few feet away. Both the underground bulbs and aerial bulbils are edible.

Growing from: Bulbils or small bulbs. Plant in fall for best establishment. Use the greens like scallions and the tiny bulbils like garlic cloves—they’re surprisingly flavorful and don’t require peeling when young.

-

Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana)

Zones: 4-8 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Indefinite

Fresh horseradish makes store-bought versions taste like pale imitations. The catch? This plant is basically indestructible once established. Even tiny root fragments will sprout new plants, so choose your location carefully or grow it in containers.

Growing from: Root cuttings planted at an angle with the larger end up. Safety tip: grate horseradish outdoors or in a well-ventilated area—the fumes are intense!

-

Chinese Artichokes (Stachys affinis)

Zones: 5-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: 3-5 years

These peculiar little spiral tubers look like they belong in a Dr. Seuss book, but they have a delightful crunchy texture and mild nutty flavor. They’re excellent pickled, stir-fried, or even eaten raw in salads.

Growing from: Tubers planted 3 inches deep in spring. They’re in the mint family and can spread aggressively—perfect for a dedicated perennial bed.

-

Sea Kale (Crambe maritima)

Zones: 4-8 | First Harvest: Year 3 | Lifespan: 10+ years

This coastal native produces thick, asparagus-like shoots when “forced” under a bucket or special terracotta forcer in late winter. The blanched shoots emerge from the underground crown system. The roots are also edible when cooked.

Growing from: Seeds (require cold stratification) or root cuttings. Sea kale was so prized in Victorian England that special pottery forcers were designed just for growing it.

-

Oca (Oxalis tuberosa)

Zones: 8-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Annual in cold zones, perennial in mild

These colorful tubers from the Andes look like jewels when you dig them up—pink, yellow, orange, and red varieties create a rainbow harvest. They have a lemony flavor when raw and become sweet and potato-like when cooked.

Growing from: Tubers planted after soil warms. Oca is day-length sensitive and only forms tubers when days are shorter than 12 hours, making it challenging in northern climates but worth the effort.

-

Skirret (Sium sisarum)

Zones: 5-9 | First Harvest: Year 2 | Lifespan: 10+ years

This forgotten medieval vegetable deserves a comeback. Skirret produces clusters of sweet, white roots that taste like a cross between parsnip and carrot with honey undertones. It was once so popular that it graced royal tables throughout Europe.

Growing from: Seeds or root divisions. Plants form clumps that can be divided every few years. The roots are best harvested after frost when sugars concentrate, and you can replant some roots to maintain the patch.

-

Arrowhead/Wapato (Sagittaria latifolia)

Zones: 3-10 | First Harvest: Year 2-3 | Lifespan: Indefinite

Also known as duck potato or Indian potato, this aquatic plant produces starchy tubers that were a staple food for Native Americans. The tubers taste like potatoes with a slightly nutty flavor and can even be made into chips.

Growing from: Tubers planted in shallow water or constantly moist soil. Each plant can produce up to 40 tubers per year once established. Traditional harvesting involves loosening tubers with your feet so they float to the surface.

-

American Groundnut (Apios americana)

Zones: 3-8 | First Harvest: Year 2-3 | Lifespan: Indefinite

This native climbing vine produces chains of protein-rich tubers along its rhizomes. The tubers were so important to early colonists that they helped some settlements survive harsh winters. They taste like a cross between potato and turnip with a slightly sweet flavor.

Growing from: Tubers planted 3-4 inches deep. The vine needs support and can climb 10-15 feet. As a legume, it fixes nitrogen in the soil, making it an excellent companion plant.

-

Welsh Onions (Allium fistulosum)

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: 5-8 years

These non-bulbing perennial onions produce thick, chive-like leaves and small underground bulbs that can both be harvested. They’re much hardier than regular onions and form attractive clumps that multiply over time.

Growing from: Seeds or divisions. Also known as bunching onions or Japanese bunching onions. The bulbs are smaller than regular onions but have an intense flavor perfect for cooking.

-

Potato Onions (Allium cepa var. aggregatum)

Zones: 5-8 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Indefinite with replanting

These multiplying onions produce clusters of bulbs from a single planted onion. They’re perfect for gardeners who want a continuous supply of cooking onions without annual planting.

Growing from: Bulbs planted in fall. Each planted onion can produce 4-8 daughter bulbs. Save some for replanting and use the rest for cooking. They have a stronger flavor than regular onions and store extremely well.

-

Wild Leeks/Ramps (Allium tricoccum)

Zones: 3-7 | First Harvest: Year 3-5 | Lifespan: Decades

The most prized wild edible in many regions, ramps have unique edible bulbs with a garlicky-onion flavor. They’re slow to establish but incredibly long-lived once settled.

Growing from: Bulbs or seeds (very slow). Requires woodland conditions with rich, moist soil and partial shade. Harvest sustainably by taking only occasional bulbs to ensure the patch continues to thrive.

-

Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum)

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: 5-10 years

These flat-leaved relatives of common chives have a mild garlic flavor and produce small underground bulbs and rhizomes in addition to their leafy harvest. The entire plant including the small bulbs is edible.

Growing from: Seeds or divisions. The flowers are edible and make stunning garnishes. The small underground bulbs develop over time and can be harvested sparingly.

-

Babington’s Leek (Allium ampeloprasum var. babingtonii)

Zones: 5-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Indefinite

This wild perennial leek produces both edible bulbs at ground level and small bulbils on top of tall flower stalks, giving you multiple underground harvests from one plant.

Growing from: Bulbils or bulbs. The plant can grow quite tall (up to 6 feet). Both the leek-like bulb at the base and the small bulbils are edible with a garlicky flavor.

-

Scorzonera (Scorzonera hispanica)

Zones: 4-8 | First Harvest: Year 2 | Lifespan: 5-8 years

Also known as black salsify, scorzonera produces long, black-skinned roots with white flesh that tastes like oysters when cooked. It’s still popular in European cuisine and makes an exotic addition to root vegetable medleys.

Growing from: Seeds sown in spring. The roots are best harvested in fall after a few frosts. The plant produces beautiful yellow daisy-like flowers if allowed to bloom.

-

Salsify (Tragopogon porrifolius)

Zones: 4-8 | First Harvest: Year 1-2 | Lifespan: Biennial, but self-seeds

Known as the vegetable oyster for its unique root flavor when cooked, salsify produces long, white roots with a delicate taste. While technically biennial, it self-seeds readily enough to function as a perennial patch.

Growing from: Seeds sown in early spring. Harvest roots in fall or winter after cold weather concentrates the flavors. The purple flowers are beautiful and the plant self-seeds readily.

-

Good King Henry (Chenopodium bonus-henricus)

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: 5-10 years

This historic vegetable was once known as “poor man’s asparagus” because its young shoots emerge from underground crowns. The thick roots are also edible when cooked, though they’re quite tough and require long cooking.

Growing from: Seeds or transplants. Once called “Lincolnshire asparagus,” the shoots emerge from underground crowns each spring. The roots develop into substantial underground storage organs.

-

Chicory (Cichorium intybus) – Root Variety

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 2 for roots | Lifespan: 5-8 years

While many know chicory leaves, the roots are the real treasure—roasted and ground as a coffee substitute or cooked as a root vegetable. Large, thick roots develop over several years.

Growing from: Seeds sown in spring. Roots are harvested in fall after 2-3 years of growth. The deep taproot helps break up compacted soil while producing your underground harvest.

-

Yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius)

Zones: 8-10 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Perennial with tuber storage

This Andean plant produces large, sweet tubers that taste like a cross between apple and jicama. The tubers are high in beneficial prebiotics and can be eaten fresh or dried.

Growing from: Tubers or divisions planted in spring. The plant looks like a small sunflower and can grow 6 feet tall. Tubers form late in the season and must be dug before hard frost in most climates.

-

Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas)

Zones: 9-11 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Perennial in frost-free areas

In tropical and subtropical climates, sweet potatoes grow as true perennials, producing tubers year-round. The traditional orange varieties and newer purple, white, and yellow types all work well.

Growing from: Slips (rooted cuttings) or vine cuttings. In colder zones, grow as an annual, but in warm climates, established plants continue producing tubers indefinitely.

Here’s How to Propagate Plants in Water: Easy Step-by-Step Method

-

Wasabi (Eutrema japonicum)

Zones: 7-10 | First Harvest: Year 2-3 | Lifespan: 5-8 years

True wasabi is grown for its rhizome, which is grated fresh for the authentic spicy condiment. It’s notoriously difficult to grow but incredibly rewarding for those who succeed.

Growing from: Plants (seeds are nearly impossible). The rhizome takes 2-3 years to reach harvestable size. Requires cool, shaded conditions with consistent moisture and excellent drainage.

Explore 36 Shade-Loving Herbs and Vegetables That Grow With Less Sunlight

-

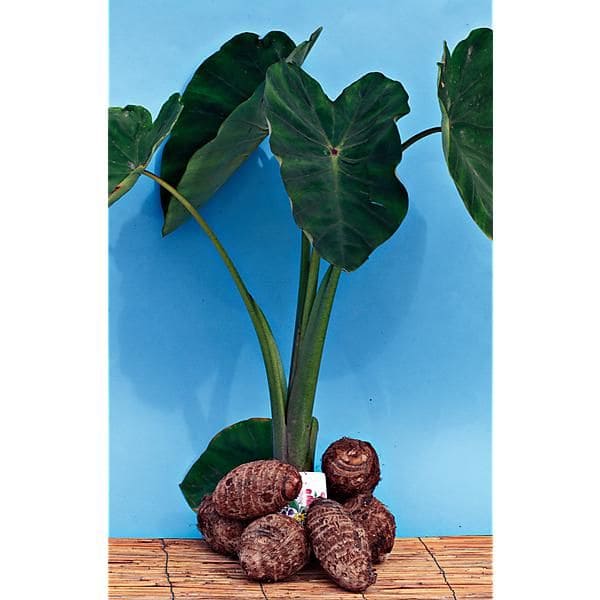

Taro (Colocasia esculenta)

Zones: 8-11 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Perennial in warm climates

This tropical plant produces large, starchy corms that are staples in many cuisines. The main corm and smaller side corms are all edible when cooked.

Growing from: Corms or divisions. Requires consistently moist soil and warm temperatures. In colder zones, grow in containers and bring indoors for winter or treat as an annual.

-

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) and Japanese Ginger (Zingiber mioga)

Zones: 8-11 for common ginger, 7-10 for Japanese ginger | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Perennial in suitable climates

While common ginger needs tropical conditions for its rhizomes, Japanese ginger (mioga) is more cold-tolerant and produces edible rhizomes with a mild ginger flavor.

Growing from: Rhizome divisions. Japanese ginger is much easier to grow in temperate climates and the rhizomes have a unique ginger-onion flavor.

-

Turmeric (Curcuma longa)

Zones: 9-11 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Perennial in warm climates

Fresh turmeric rhizomes have a much more complex flavor than dried powder and are increasingly popular. The rhizomes are the prized underground harvest.

Growing from: Rhizome pieces with growing points. Requires warm, humid conditions and rich, well-draining soil. In colder climates, grow in containers and bring indoors for winter.

-

Daylily (Hemerocallis spp.)

Zones: 3-9 | First Harvest: Year 2 | Lifespan: Decades

While primarily grown for ornamental flowers, daylilies produce edible tubers and thick roots underground. The tubers can be cooked like small potatoes and have a mildly sweet flavor.

Growing from: Divisions or bare-root plants. The underground tubers develop over several years and can be harvested sparingly. Only eat plants you know haven’t been treated with chemicals.

Find out How and Why to Deadhead Daylilies for Boosting Blooms

-

Dahlia (Dahlia spp.) – Edible Tuber Varieties

Zones: 8-11 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Perennial with tuber storage

While famous for their flowers, dahlia tubers are edible and were originally grown as food crops by the Aztecs. They have a crunchy texture and mildly sweet flavor.

Growing from: Tubers planted after soil warms. The tubers contain inulin (like Jerusalem artichokes) and can cause digestive upset in some people. Try small amounts first.

-

Hamburg Parsley (Petroselinum crispum var. tuberosum)

Zones: 4-8 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Biennial, but can be maintained as perennial

Also called parsley root, this variety produces thick, white roots that taste like a cross between parsley and parsnip. The roots are the main harvest, though the leaves are also edible.

Growing from: Seeds sown in spring. Roots develop over the growing season and are best harvested after frost. Can be maintained by allowing some plants to go to seed for continuous harvest.

-

Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum spp.)

Zones: 3-8 | First Harvest: Year 3-4 | Lifespan: Decades

This elegant woodland plant produces young shoots from underground rhizomes that can be cooked like asparagus, and the rhizomes themselves are edible when properly prepared.

Growing from: Plants or divisions. Requires shade and moist, rich soil. The rhizomes were traditionally prepared by indigenous peoples as a starchy food source.

-

Common Camas (Camassia quamash)

Zones: 3-8 | First Harvest: Year 3-5 | Lifespan: Decades

This beautiful flowering bulb native to western North America produces edible bulbs that were a crucial food source for Native Americans. The bulbs are sweet when properly cooked but require long cooking times (12-36 hours).

Growing from: Bulbs planted in fall. The deep blue flowers are stunning in spring. Bulbs should only be harvested from established patches and require traditional pit-cooking methods for best results.

-

Mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum)

Zones: 8-10 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Annual in cold zones, perennial in mild

This Andean climbing nasturtium produces colorful tubers with a peppery, slightly bitter flavor. The tubers come in yellow, purple, and speckled varieties.

Growing from: Tubers planted in spring. The vine produces beautiful flowers and can climb 6-8 feet. Tubers form late in the season and need long days to develop properly.

-

Ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus)

Zones: 9-10 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: Annual in cold zones, perennial in mild

Another Andean root crop producing small, brightly colored tubers that range from yellow to pink to purple. They have a crispy texture and mild flavor.

Growing from: Tubers planted after soil warms. Very day-length sensitive and requires short days to form tubers. The colorful tubers are often called “earth gems.”

-

Pacific Waterleaf (Hydrophyllum tenuipes)

Zones: 7-10 | First Harvest: Year 2-3 | Lifespan: Decades

This shade-loving native produces edible rhizomes with a flavor similar to Chinese bean sprouts. The rhizomes spread underground, creating patches that can be harvested sustainably.

Growing from: Plants or seeds. Prefers woodland conditions with moist, rich soil. The white rhizome tips are the most tender and flavorful parts.

-

Elephant Garlic (Allium ampeloprasum)

Zones: 4-9 | First Harvest: Year 1 | Lifespan: 5-8 years

Despite its name, elephant garlic is actually a type of leek that produces enormous bulbs with a mild garlic flavor. The bulbs can weigh over a pound and store for months.

Growing from: Cloves planted in fall like regular garlic. Each planted clove produces a large bulb plus several smaller bulbils that can be replanted to maintain the patch.

Designing Your Perennial Root Vegetable Garden

The Dedicated Bed Approach

The simplest way to incorporate perennial root vegetables is to create a dedicated perennial bed separate from your annual vegetable garden. This prevents the disruption that comes with yearly tillage and replanting.

A 4×8 foot bed can comfortably hold 4-6 asparagus crowns, 1 rhubarb plant, 3-4 walking onion clumps, and 2-3 Jerusalem artichoke plants.

Learn Hügelkultur 101: Step‑by‑Step Guide to Building Self-Sustaining Raised Garden Beds

The Food Forest Integration

For a more ambitious approach, integrate your perennial root vegetables into a food forest design. Plant them as the understory layer beneath fruit trees, alongside berry bushes, and between perennial herbs. This creates a layered ecosystem that mimics natural forests while maximizing food production.

Discover Atlanta’s Largest Free Food Forest: A Sustainable Urban Oasis

Container Growing Solutions

Don’t have in-ground space? Many perennial root vegetables adapt well to large containers. Sorrel, chives, and smaller Jerusalem artichokes thrive in containers, while dwarf rhubarb varieties can succeed in minimum 20-gallon containers. Remember that containers dry out faster and may need winter protection in cold climates.

Read the Delayed Planting Guide: Tips for Successful Container Tree Care

Planting and Establishment: Setting Your Plants Up for Success

Soil Preparation: The Foundation of Success

I learned this lesson the expensive way when my first asparagus planting failed spectacularly. Perennial root vegetables will be in the same spot for years, so soil preparation is crucial. It’s like the difference between building a house on sand versus on bedrock.

Start by testing your soil pH—most perennials prefer slightly acidic to neutral soil (6.0-7.0). Add 2-4 inches of compost to improve drainage in clay soil and water retention in sandy soil. Incorporate slow-release organic fertilizer (a balanced 10-10-10 organic fertilizer works for most), and ensure good drainage since perennial roots hate sitting in water.

Timing Your Plantings for Success

Spring plantings from March to May work best for asparagus crowns, Jerusalem artichoke tubers, horseradish root cuttings, and sorrel seeds or transplants. Fall plantings from September to November are ideal for walking onion bulbils, rhubarb crowns, and globe artichoke transplants in mild climates.

The First Year: Patience and Establishment

The first year is all about root development, not harvest. Resist the urge to harvest heavily (or at all, in the case of asparagus). Think of it as an investment—you’re building the foundation for years of future abundance.

Keep soil consistently moist but not waterlogged, mulch around plants to suppress weeds and retain moisture, remove flower stalks (except on plants grown for flowers), and most importantly, be patient!

Harvesting: The Art of Sustainable Abundance

The Sustainable Harvest Principle

For leafy perennials like sorrel and perennial kale, never harvest more than one-third of the plant’s foliage at one time. This ensures the plant maintains enough photosynthetic capacity to sustain itself and continue growing.

Root Crop Harvesting Strategies

For tubers and bulbs like Jerusalem artichokes and walking onions, harvest what you need while leaving the rest to multiply. Always leave some smaller tubers or bulbs for next year’s crop, and mark your beds so you remember where things are planted—especially important after the tops die back.

For crown crops like asparagus and rhubarb, harvest during the plant’s active season but stop when spears become thin (asparagus) or when summer heat arrives (rhubarb). Allow plants to fern out and photosynthesize for next year’s energy storage.

Seasonal Harvesting Guide

- Early Spring: Asparagus spears, forced sea kale shoots, and young sorrel leaves lead the season.

- Late Spring: Continue with rhubarb stalks, walking onion greens and bulbils, plus ongoing asparagus harvest.

- Summer: Globe artichoke buds, Chinese artichoke greens, and heat-tolerant sorrel varieties.

- Fall: The big harvest season for Jerusalem artichoke tubers, horseradish roots, and oca tubers after first frost.

- Winter: Enjoy stored root vegetables, forced sea kale, and protected sorrel in mild climates.

Find out When and How to Harvest Vegetables for Peak Flavor: Timing and Tips for Every Crop

Storage and Preservation: Extending Your Harvest

Root Vegetable Storage Methods

Jerusalem artichokes store best in the ground until needed—just mark the rows with stakes. Once dug, they keep for weeks in the refrigerator wrapped in damp paper towels. Horseradish roots can be stored in damp sand in a cool cellar for months, while oca tubers should be cured in sunlight for a few days before storing in a cool, dry place.

Preserving Your Bounty

Rhubarb freezes beautifully when chopped and stored in freezer bags—no need to blanch. Sorrel can be turned into sorrel soup and frozen, or dried for winter seasoning. Jerusalem artichokes can be pickled, fermented, or dried and ground into flour for a nutty addition to baked goods.

Pest and Disease Management: Keeping Your Plants Healthy

Prevention Is Your Best Defense

Healthy, well-established perennial plants are naturally more resistant to pests and diseases. Ensure good air circulation between plants, avoid overhead watering when possible, and maintain soil health with regular compost additions.

Common Issues and Solutions

Asparagus beetles can be handpicked or controlled with beneficial nematodes. Aphids on globe artichokes respond well to strong water sprays or beneficial insects like ladybugs.

Root maggots in Jerusalem artichokes are usually prevented by good drainage and avoiding fresh manure. Slug damage on sorrel and sea kale can be managed with copper barriers or diatomaceous earth.

Regional Considerations

In humid climates, focus on improving air circulation and choosing disease-resistant varieties. In dry climates, ensure adequate moisture during establishment and mulch heavily to retain soil moisture. Cold climate gardeners should choose the hardiest varieties and provide winter protection for marginally hardy plants.

Winter Care and Protection

Preparing Plants for Winter

Most perennial root vegetables benefit from a 2-4 inch layer of compost or aged manure applied in late fall. This provides slow-release nutrients for spring growth while protecting crowns from temperature fluctuations.

Cold Climate Strategies

In zones 5 and colder, cover marginally hardy plants like globe artichokes with a thick layer of straw or leaves. Container-grown plants may need to be moved to an unheated garage or wrapped with insulation. Cut back dead foliage but leave some stems to mark plant locations.

Extending the Growing Season

Cold frames or row covers can extend harvests of sorrel and other leafy perennials well into winter. Forcing techniques work well for sea kale and rhubarb—cover crowns with buckets or special forcers in late winter for early, tender harvests.

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

“My Plants Aren’t Producing Much”

Poor production usually stems from impatience (many perennials take 2-3 years to reach full production), poor soil conditions (amend with compost and ensure proper drainage), insufficient sunlight (ensure 6+ hours for most varieties), or over-harvesting in early years (allow plants to build energy reserves).

“Everything’s Taking Over My Garden!”

Some perennial root vegetables are enthusiastic spreaders. Jerusalem artichokes, walking onions, and horseradish all fall into this category. Manage them by planting in dedicated beds with barriers, using large containers sunk into the ground, harvesting regularly to control spread, or choosing less aggressive varieties when available.

“I Can’t Find These Plants Anywhere!”

Many perennial root vegetables aren’t available at typical garden centers. Try online specialty nurseries like Baker Creek, Johnny’s Seeds, or Fedco Seeds.

Local plant swaps are excellent sources since many perennial vegetables are easily shared between gardeners. Join specialty food groups or Facebook communities focused on unusual edibles, or start from seed when possible—though it takes longer.

“My Family Won’t Eat Weird Vegetables”

Start with familiar flavors and gradually introduce more unusual varieties. Begin with gateway vegetables like asparagus, rhubarb, and walking onions that taste like regular onions.

Preparation matters enormously—Jerusalem artichokes are much more palatable when roasted until caramelized rather than boiled. Mix new flavors with familiar foods by adding sorrel to regular salad mixes or using walking onion greens in place of chives.

Advanced Techniques for Maximum Success

Succession Planting with Perennials

While you can’t succession plant the same perennial, you can create overlapping harvests by planting early and late varieties, combining spring-harvested crops like rhubarb with fall-harvested ones like Jerusalem artichokes, and mixing quick-producing plants like sorrel with slow-establishing ones like asparagus.

Companion Planting Benefits

Perennial root vegetables play well with others when you choose the right companions. Comfrey acts as a dynamic accumulator, bringing nutrients up from deep soil layers.

Nasturtiums and marigolds provide natural pest deterrence while attracting beneficial insects. Asparagus famously grows well with tomatoes, while rhubarb companions beautifully with roses.

Renovation and Rejuvenation

Even perennials need occasional refreshing to maintain peak production. Divide clumping plants every 3-5 years to maintain vigor—this is especially important for rhubarb and walking onions.

Refresh soil annually with compost additions and replace declining plants before they become unproductive. Keep detailed records of planting dates and varieties for future planning and troubleshooting.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q: How much space do I need for a perennial root vegetable garden?

A: You can start with as little as a 4×4 foot bed. This would accommodate 2-3 asparagus crowns, 1 rhubarb plant, and a few smaller perennials like sorrel or chives. The key is choosing plants that match your space and growing them vertically when possible.

- Q: Are perennial root vegetables worth it if I might move in a few years?

A: Absolutely! Even if you only get 2-3 years of harvest, many perennials will pay for themselves in that time. Plus, established perennial beds can be a selling point for your home—imagine advertising a house with a mature asparagus bed!

- Q: What if I live in an apartment or have no yard space?

A: Many perennial root vegetables adapt well to large containers. Sorrel, chives, and smaller varieties of Jerusalem artichokes can thrive in pots. You can even grow dwarf rhubarb varieties in large containers (minimum 20 gallons).

- Q: How do I know if my climate is suitable for these plants?

A: Check the USDA hardiness zones listed for each plant and compare them to your area. When in doubt, start with the most cold-hardy options (asparagus, rhubarb, walking onions) and experiment with more tender varieties as you gain experience.

- Q: Do perennial vegetables require special fertilizers?

A: Most perennial root vegetables are fairly low-maintenance once established. An annual application of compost in early spring, plus occasional feeding with balanced organic fertilizer, is usually sufficient. Avoid high-nitrogen fertilizers, which can encourage leaf growth at the expense of root development.

Your Perennial Root Vegetable Adventure Starts Now

Starting a perennial root vegetable garden is like planting seeds for your future self. It requires some upfront planning and patience, but the payoff—fresh, homegrown food with minimal ongoing effort—is remarkable.

My advice? Start small, choose varieties that match your climate and cooking style, and remember that every expert was once a beginner. That first spring when your asparagus spears push through the soil or when you dig up a bucket of Jerusalem artichokes from a plant you forgot you even had—those moments make all the initial effort worthwhile.

The best time to plant perennial root vegetables was ten years ago. The second-best time is right now. Choose one or two varieties from this guide, prepare a small bed this fall or spring, and take the first step toward a more sustainable, abundant garden. Your future self—and your back—will thank you.

What perennial root vegetable are you most excited to try? Share your experiences or questions in the comments below, and let’s grow this community of perennial gardeners together!